A Deep Dive into Routing and Controller Dispatch in Rails

Originally published on Ruby Inside

Rails has a lot of magic that we often take for granted. A lot is going on the behind the clever, elegant abstractions that Rails provides us as users of the framework. And at a certain point, I find it’s useful to peek behind the curtain and see how things really work.

But opening the Rails source code can be absolutely daunting at first. It can feel like a jungle of abstractions and metaprogramming. A large part of this is due to the nature of object-oriented programming: by its nature, it’s not easy to follow a step-by-step path that would be taken at runtime. Sometimes, it helps to have a guide.

With this in mind, let’s take some time to explore how routing works in Rails. How does a web request accepted by Rack make it all the way to your Rails controller?

Familiar territory

For the purposes of this example, consider a Rails app with a single route and controller:

class UsersController < ApplicationController

def index

# ...

end

end

# config/routes.rb

Rails.application.routes.draw do

resources :users, only: [:index]

end

In this app, a GET request to /users will be routed to the UsersController. But how?

Orientation

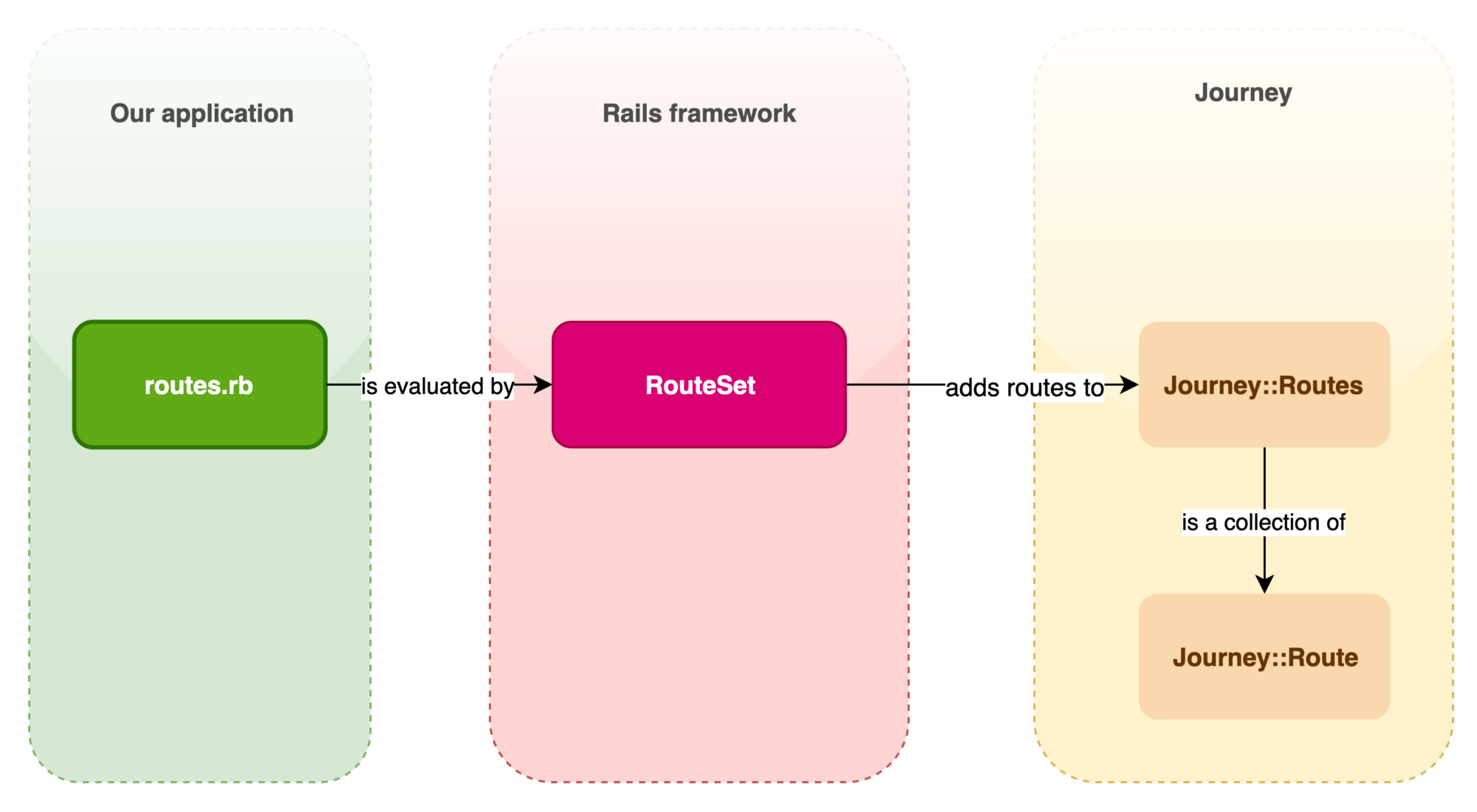

A lot of collaboration happens to get from request to controller, so it will be useful to get a bird’s eye view before diving in. Here’s a diagram that shows how routes defined in routes.rb are registered within Rails at boot time. We’ll explore these classes in more detail shortly:

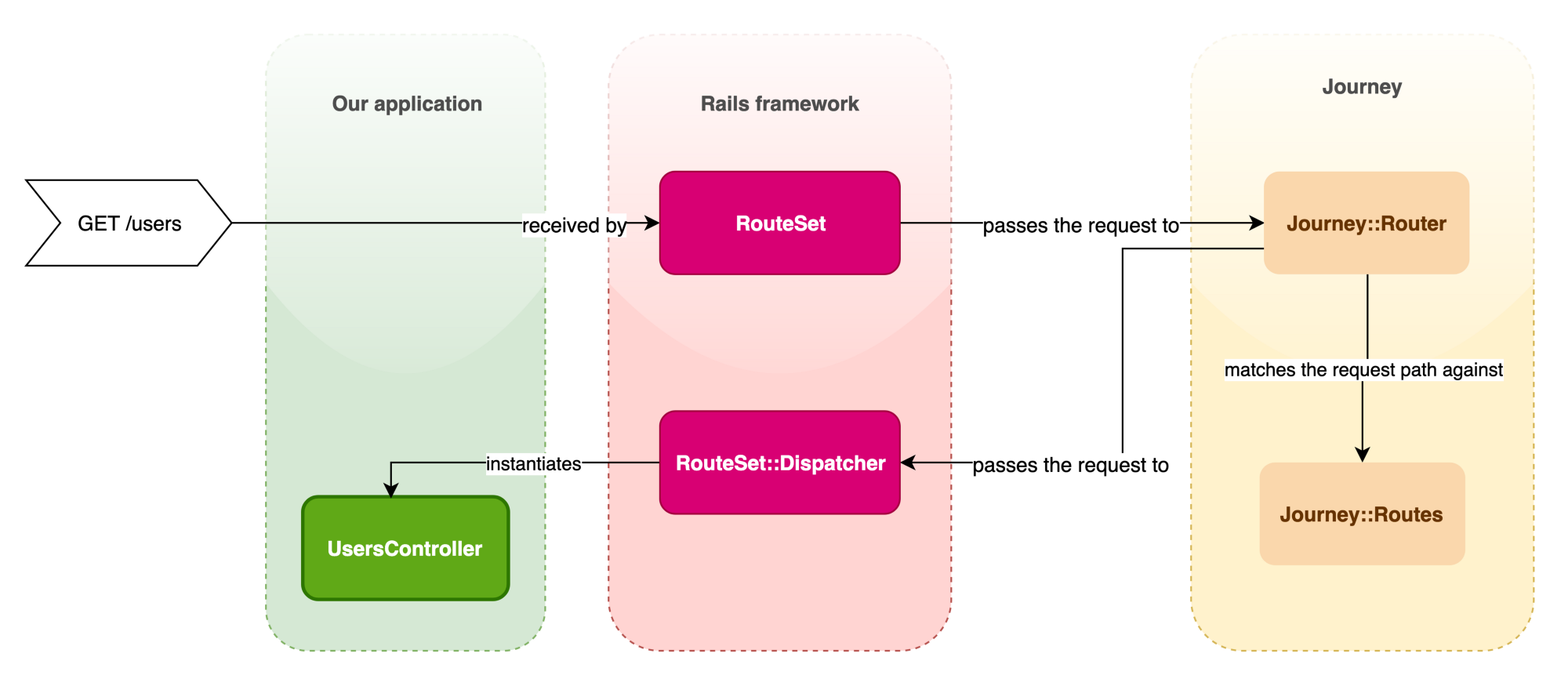

And here’s the sequence of events that occurs when we make our GET request to /users:

routes.rb

The file you know and love! From a Rails framework perspective, this is the public interface. Declare your routes in this file, and Rails will take care of figuring out how to route a request to the right controller.

RouteSet

I kind of lied when I said routes.rb was the public interface. It’s really a DSL to the public interface. The RouteSet is the actual class that acts as the entry point for route configuration in a Rails application. It’s most famous for the #draw method, which we’ve just used in routes.rb:

# What's Rails.application.routes? Why, an instance of `RouteSet`, of course!

Rails.application.routes.draw do

# ...

end

Journey::Routes

Once upon a time, Journey was a standalone gem, before it was merged into ActionPack. It focuses on routes, and figuring out how to route an incoming request. It doesn’t know about Rails at all, nor does it care — give it a set of routes, then pass it a request, and it will route that request to the first route that matches.

How it performs the routing in an efficient way is fascinating, and there’s a great talk from Vaidehi Joshi that goes into detail on the internals of Journey. I highly recommend it!

Journey::Routes holds on to the routes that our Rails app knows about. RouteSet delegates to it whenever a new route is registered at startup, whether that’s from routes.rb, an engine, or a gem like Devise that defines its own routes.

Journey::Route

If we think of Journey::Routes like an array, then Journey::Route objects are the elements inside. In addition to the metadata you’d expect this object to hold on to, like the path of the route, it also holds a reference to app, which will get invoked if that route is chosen to serve the request.

In this way, each Journey::Route is kind of like a tiny web app that responds to a single endpoint. It has no knowledge of other routes aside from its own, but it can guide our request in the right direction when the time comes.

RouteSet::Dispatcher

Contrary to what you might think, the app that lives inside of each Journey::Route object is not some reference to the controller. There’s one more level of indirection here, as a means of keeping Rails code separate from the routing logic that Journey concerns itself with.

Dispatcher is a small class which is responsible for instantiating the controller and passing along our request, along with an empty response object. It’s invoked when a suitable route is identified for a request. It has no knowledge about how a request arrived on its doorstep, but it knows what to do when it sees our request: instantiate the UsersController and hand it our request. As we’ll see, it acts as an object factory for our controllers, removing the need for us to declare our controller classes anywhere outside of the classes themselves.

This might seem like an almost needless indirection, but it’s worthwhile considering that Dispatcher’s position between routing logic and controller classes allows either to change without affecting the other.

Journey::Router

Journey::Routes knows nothing about requests. It knows about routes, and it will quickly and efficiently identify the correct one for the request. So in order to map an incoming request to a route, we need something that knows about a request and a route. Enter Router.

It’s Router that actually invokes the Dispatcher once a route has been found.

UsersController

Hey, we know what this is already! Welcome home. 😌 Now let’s connect the dots.

Back to where it all began…

Let’s circle back to our routes file:

Rails.application.routes.draw do

resources :users, only: [:index]

end

When Rails is booting, a new RouteSet gets instantiated. It evaluates the contents of the routes file and builds up a RouteSet.

Because RouteSet is the source of truth for all available endpoints in our application, it’s also first in line to receive a request from the outside world, after passing through Rack and various middleware. That’s right, this humble class buried in ActionPack is the Walmart greeter of our application, ready with a smile and a wave as soon as a request comes through the door.

In order for RouteSet to accept the request after it’s travelled through Rack and any middleware, it needs to implement Rack’s interface, which is as simple as implementing call (source):

def call(env)

req = make_request(env)

req.path_info = Journey::Router::Utils.normalize_path(req.path_info)

@router.serve(req)

end

Here we build a new request object. This will end up being a fresh instance of ActionDispatch::Request, populated from env, which is the incoming hash that Rack serves us.

After doing some string gymnastics on the incoming path, we pass the request off to @router, which is an instance of Journey::Router. We pass it a request and ask it to serve that request.

In Journey::Router#serve, we iterate through the routes that match the path in the request (source):

def serve(req)

find_routes(req).each do |match, parameters, route|

set_params = req.path_parameters

# ...

req.path_parameters = set_params.merge parameters

# ...

status, headers, body = route.app.serve(req)

# ...

return [status, headers, body]

end

[404, { "X-Cascade" => "pass" }, ["Not Found"]]

end

Pay special attention to this line:

req.path_parameters = set_params.merge parameters

req.path_parameters is now a hash that might look familiar:

{:controller=>"users", :action=>"index"}

Notice that we’re actually enriching the request object itself with metadata that’s returned from the find_routes method. This is quite subtle, but it’s how Journey communicates with the rest of the system. Once it identifies a matching route for the request, it “stamps” that knowledge onto the request itself, so that subsequent objects that deal with the request (like Dispatcher) know how to proceed. Foreshadowing!

Anyway, when a match is finally found, we ask the route’s app to serve the request, then return the familiar array from any Rack app of status, headers, and body.

The reason for all this indirection is separation of concerns. In theory, Journey can function perfectly fine outside of a Rails application, and as a result it’s abstracted the concept of an “app” into anything that implements Rack’s interface.

It’s here that Rails comes back into the picture. As I mentioned before, each object behind route.app is actually an instance of Dispatcher (source):

class Dispatcher < Routing::Endpoint

# ...

def serve(req)

params = req.path_parameters

controller = controller req

res = controller.make_response! req

dispatch(controller, params[:action], req, res)

rescue ActionController::RoutingError

if @raise_on_name_error

raise

else

[404, { "X-Cascade" => "pass" }, []]

end

end

private

def controller(req)

req.controller_class

rescue NameError => e

raise ActionController::RoutingError, e.message, e.backtrace

end

def dispatch(controller, action, req, res)

controller.dispatch(action, req, res)

end

end

Dispatcher is our entry point back into Rails land. It knows that a request is served by a controller, and it knows that the way to talk to a Rails controller is to send it a #dispatch method and pass along the action, the request object, and a fresh new ActionDispatch::Response object to write the response into.

Notice that in the #controller method above, we punt the question of which class to use to the request itself. When our request was first born, it had no idea who should be handling its request; it was just a glorified hash with a ton of metadata coming from the outside world. But thankfully, it passed through Journey’s hands, who imbued it with a few crucial pieces of data:

req.path_parameters

=> {:controller=>"users", :action=>"index"}

Armed with this knowledge, the request object itself is now in a position to answer the question, “which controller should serve my request?”

Here’s what that looks like in the Request object (source):

# actionpack/lib/action_dispatch/http/request.rb

def controller_class_for(name)

if name

controller_param = name.underscore

const_name = "#{controller_param.camelize}Controller"

ActiveSupport::Dependencies.constantize(const_name)

else

PASS_NOT_FOUND

end

end

Buried deep in the Rails framework is a great example of the Factory Pattern at work. We want to automagically choose the right class to handle our incoming request, and we don’t want to hardcode a list of all of our controllers anywhere, because that would be a pain. Since we now have a string, “users”, that tells us which controller this request wants to go to, we can build up the official class name, UsersController, and use #constantize to turn that into the class constant. Along with help from Dispatcher, which ends up invoking the method above, we have a way of instantiating the right controller for the request at runtime.

This is also a great example of the Open/Closed principle. Since Rails makes the assumption that your controllers are going to be named a certain way, you’re free to define a new controller simply by creating a new class that follows the naming convention, and defining its matching route. At no point do you have to update some ungainly mapping of route -> controller, or even register your controller anywhere. It’s the adherence to this principle that powers the Rails mantra of convention over configuration.

Now we’re getting really close: a message has been sent to the UsersController! Through a series of intermediary methods, we finally invoke the method #index on the controller:

# actionpack/lib/action_controller/metal.rb

def dispatch(name, request, response) #:nodoc:

set_request!(request)

set_response!(response)

process(name)

# ...

end

# actionpack/lib/abstract_controller/base.rb

def process(action, *args)

# ...

process_action(action_name, *args)

end

def process_action(method_name, *args)

send_action(method_name, *args)

end

alias send_action send

It looks like a lot, but ultimately we’re just using Ruby’s send method to invoke the correct action on our controller instance. Simplified, it might look something like this:

UsersController.new(request, response).send(:index)

Unwinding the Abstraction

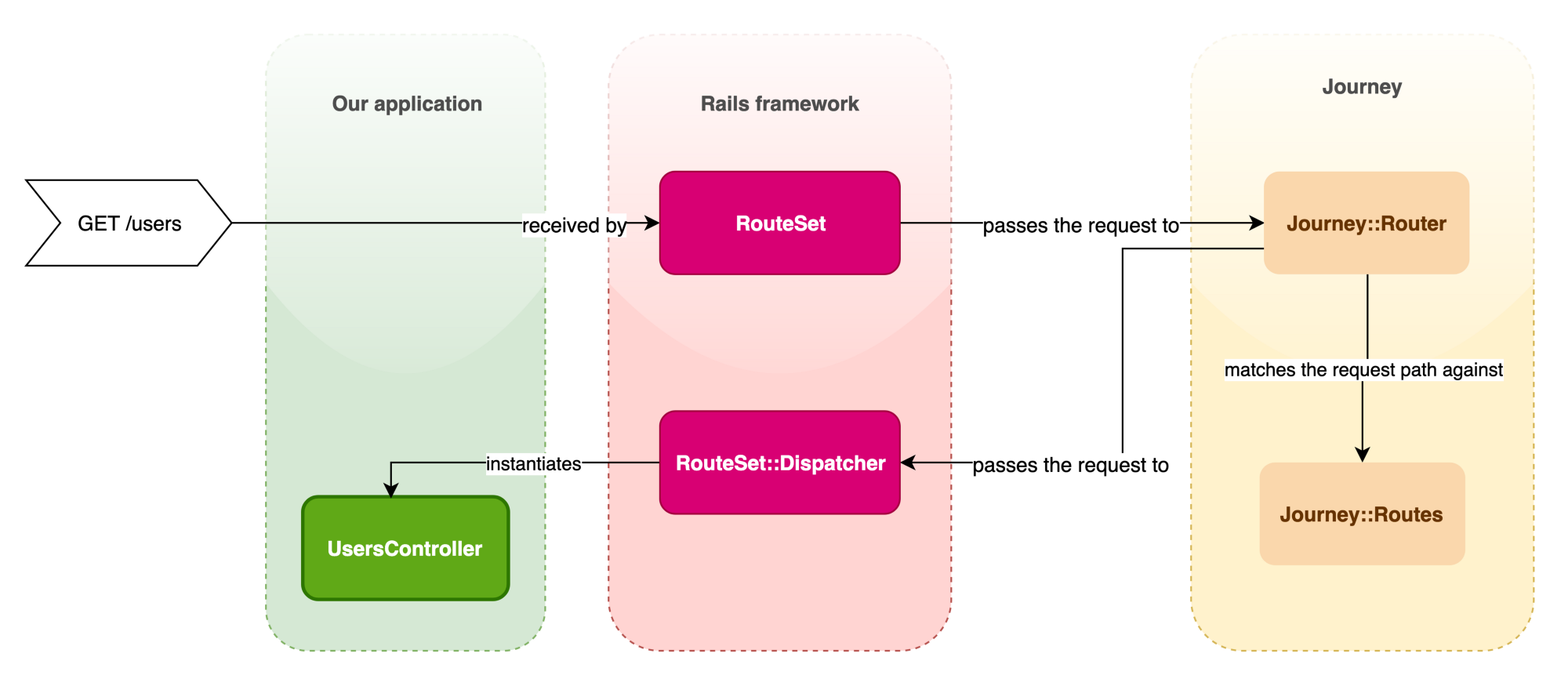

We just looked at a lot of objects. It can be hard to follow the path of execution when we need to bounce around so many different files. As a reminder, here’s the sequence of events again:

Another way to help clarify our understanding could be to reduce all of these steps down to a single method. Stripping away some of the abstraction, it might end up looking something like this:

# remember that this is totally fake and you won't find this code anywhere in Rails ;)

def call(env)

req = ActionDispatch::Request.new(env)

res = ActionDispatch::Response.new(req)

find_routes(req).each do |match, parameters, route|

controller_name = "#{parameters[:controller]}Controller".constantize # UsersController

action = parameters[:action] # "index"

controller = controller.new(req, res)

status, headers, body = controller.send(action)

return [status, headers, body]

end

end

Conclusion

If you made it this far, congratulations! 🎉 As you can see, there’s a lot going on behind the scenes, but hopefully this has helped to demystify some of the magic and appreciate the object-oriented principles at work.

Next time you add a new controller to your Rails app, sit back and appreciate just how much heavy lifting Rails is doing to take care of the details.

If you want to explore this code further, run bundle open actionpack from your Rails app’s directory and have a look at the classes we’ve explored, or check out the actionpack code on GitHub. Have fun!