A Deep Dive into CSRF Protection in Rails

Originally published on Ruby Inside. Updated in June 2019 to reflect code changes in Rails 6

If you’re using Rails today, chances are you’re using CSRF protection. It’s been there almost since the beginning, and it’s one of those features in Rails that makes your life easier without needing to give it a second thought.

Briefly, Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) is an attack that allows a malicious user to spoof legitimate requests to your server, masquerading as an authenticated user. Rails protects against this kind of attack by generating unique tokens and validating their authenticity with each submission.

Recently, I was working on a feature at Unbounce that required me to think about CSRF protection and how we were handling it in client-side Javascript requests. It was then that I realized how little I actually knew about it, beyond what the acronym stands for!

I decided to do a deep-dive into the Rails codebase to understand how the feature has been implemented. What follows is an exploration of how CSRF protection works in Rails. We’ll look at how the tokens are initially generated for each response, and how they’re used on an incoming request to validate the authenticity of the request.

The Basics

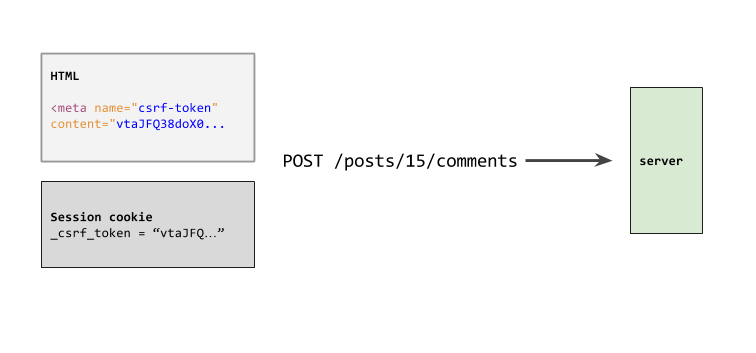

There are two components to CSRF. First, a unique token is embedded in your site’s HTML. That same token is also stored in the session cookie. When a user makes a POST request, the CSRF token from the HTML gets sent with that request. Rails compares the token from the page with the token from the session cookie to ensure they match.

How you use it

As a Rails developer, you basically get CSRF protection for free. It starts with this single line in application_controller.rb, which enables CSRF protection:

protect_from_forgery with: :exception

Next, there’s this single line in application.html.erb:

<%= csrf_meta_tags %>

… and that’s it. This has been in Rails for ages, and so we barely need to think about it. But how is this actually implemented under the hood?

Generation and Encryption

We’ll start with #csrf_meta_tags. It’s a simple view helper that embeds the authenticity token into the HTML:

# actionview/lib/action_view/helpers/csrf_helper.rb

def csrf_meta_tags

if defined?(protect_against_forgery?) && protect_against_forgery?

[

tag("meta", name: "csrf-param", content: request_forgery_protection_token),

tag("meta", name: "csrf-token", content: form_authenticity_token)

].join("\n").html_safe

end

end

The csrf-token tag is what we’re going to focus on, since it’s where all the magic happens. That tag helper calls #form_authenticity_token to grab the actual token. At this point, we’ve entered ActionController’s RequestForgeryProtection module. Time to have some real fun!

The RequestForgeryProtection module handles everything to do with CSRF. It’s most famous for the #protect_from_forgery method you see in your ApplicationController, which sets up some hooks to make sure that CSRF validation is triggered on each request, and how to respond if a request isn’t verified. But it also takes care of generating, encrypting and decrypting the CSRF tokens. What I like about this module is its small scope; aside from some view helpers, you can see the whole implementation of CSRF protection right in this single file.

Let’s continue diving into how the CSRF token ends up in your HTML. #form_authenticity_token is a simple wrapper method that passes any optional parameters, as well as the session itself, down into #masked_authenticity_token:

# actionpack/lib/action_controller/metal/request_forgery_protection.rb

# Sets the token value for the current session.

def form_authenticity_token(form_options: {})

masked_authenticity_token(session, form_options: form_options)

end

# Creates a masked version of the authenticity token that varies

# on each request. The masking is used to mitigate SSL attacks

# like BREACH.

def masked_authenticity_token(session, form_options: {}) # :doc:

# ...

raw_token = if per_form_csrf_tokens && action && method

# ...

else

real_csrf_token(session)

end

one_time_pad = SecureRandom.random_bytes(AUTHENTICITY_TOKEN_LENGTH)

encrypted_csrf_token = xor_byte_strings(one_time_pad, raw_token)

masked_token = one_time_pad + encrypted_csrf_token

Base64.strict_encode64(masked_token)

end

Since the introduction of per-form CSRF tokens in Rails 5, the #masked_authenticity_token method has gotten a bit more complex. For the purposes of this exploration, we’re going to focus on the original implementation, a single CSRF token per request - the one that ends up in the meta tag. In that case, we can just focus on the else branch of the conditional above, which ends up setting raw_token to the return value of #real_csrf_token.

Why do we pass session into #real_csrf_token? Because this method actually does two things: it generates the raw, unencrypted token, and it stuffs that token into the session cookie:

# actionpack/lib/action_controller/metal/request_forgery_protection.rb

def real_csrf_token(session) # :doc:

session[:_csrf_token] ||= SecureRandom.base64(AUTHENTICITY_TOKEN_LENGTH)

Base64.strict_decode64(session[:_csrf_token])

end

Remember that this method is ultimately being called because we invoked #csrf_meta_tags in our application layout. This is classic Rails Magic - a clever side effect that guarantees the token in the session cookie will always match the token on the page, because rendering the token to the page can’t happen without inserting that same token into the cookie.

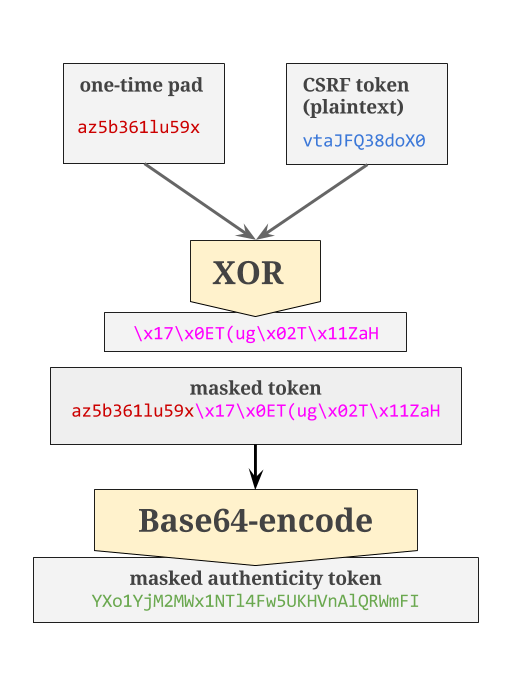

Anyway, let’s take a look at the bottom of #masked_authenticity_token:

one_time_pad = SecureRandom.random_bytes(AUTHENTICITY_TOKEN_LENGTH)

encrypted_csrf_token = xor_byte_strings(one_time_pad, raw_token)

masked_token = one_time_pad + encrypted_csrf_token

Base64.strict_encode64(masked_token)

Time for some cryptography. Having already inserted the token into the session cookie, this method now concerns itself with returning the token that will end up in plaintext HTML, and here we take some precautions (mainly to mitigate the possibility of an SSL BREACH attack, which I won’t go into here). Note that we didn’t encrypt the token that goes into the session cookie, because as of Rails 4 the session cookie itself will be encrypted.

First, we generate a one-time pad that we’ll use to encrypt the raw token. A one-time pad is a cryptographic technique that uses a randomly-generated key to encrypt a plaintext message of the same length, and requires the key to be used to decrypt the message. It’s called a “one-time” pad for a reason: each key is used for a single message, and then discarded. Rails implements this by generating a new one-time pad for every new CSRF token, then uses it to encrypt the plaintext token using the XOR bitwise operation. The one-time pad string is prepended to the encrypted string, then Base64-encoded to make the string ready for HTML.

Once this operation is complete, we send the masked authenticity token back up the stack, where it ends up in the rendered application layout:

<meta name="csrf-param" content="authenticity_token" />

<meta name="csrf-token" content="vtaJFQ38doX0b7wQpp0G3H7aUk9HZQni3jHET4yS8nSJRt85Tr6oH7nroQc01dM+C/dlDwt5xPff5LwyZcggeg==" />

Decryption and verification

So far, we’ve covered how the CSRF token is generated, and how it ends up in your HTML and cookie. Next, let’s look at how Rails validates an incoming request.

When a user submits a form on your site, the CSRF token is sent along with the rest of the form data (a param called authenticity_token by default). It can also be sent via the X-CSRF-Token HTTP header.

Recall this line in our ApplicationController:

protect_from_forgery with: :exception

Among other things, this #protect_from_forgery method adds a before-action to the lifecycle of every controller action:

before_action :verify_authenticity_token, options

This before action begins the process of comparing the CSRF token in the request params or header with the token in the session cookie:

# actionpack/lib/action_controller/metal/request_forgery_protection.rb

def verify_authenticity_token # :doc:

# ...

if !verified_request?

# handle errors ...

end

end

# ...

def verified_request? # :doc:

!protect_against_forgery? || request.get? || request.head? ||

(valid_request_origin? && any_authenticity_token_valid?)

end

After performing some administrative tasks (we don’t need to verify HEAD or GET requests, for example), our verification process begins in earnest with the call to #any_authenticity_token_valid?:

def any_authenticity_token_valid? # :doc:

request_authenticity_tokens.any? do |token|

valid_authenticity_token?(session, token)

end

end

Since a request can pass the token in form params or as a header, Rails just requires that at least one of those tokens match the token in the session cookie.

#valid_authenticity_token? is a pretty long method, but ultimately it’s just doing the inverse of #masked_authenticity_token in order to decrypt and compare the token:

def valid_authenticity_token?(session, encoded_masked_token) # :doc:

# ...

begin

masked_token = Base64.strict_decode64(encoded_masked_token)

rescue ArgumentError # encoded_masked_token is invalid Base64

return false

end

if masked_token.length == AUTHENTICITY_TOKEN_LENGTH

# ...

elsif masked_token.length == AUTHENTICITY_TOKEN_LENGTH * 2

csrf_token = unmask_token(masked_token)

compare_with_real_token(csrf_token, session) ||

valid_per_form_csrf_token?(csrf_token, session)

else

false # Token is malformed.

end

end

First, we need to take the Base64-encoded string and decode it to end up with the “masked token”. From here, we unmask the token and then compare it to the token in the session:

def unmask_token(masked_token) # :doc:

one_time_pad = masked_token[0...AUTHENTICITY_TOKEN_LENGTH]

encrypted_csrf_token = masked_token[AUTHENTICITY_TOKEN_LENGTH..-1]

xor_byte_strings(one_time_pad, encrypted_csrf_token)

end

Before #unmask_token can perform the cryptography magic necessary to decrypt the token, we have to split the masked token into its requisite parts: the one-time pad, and the encrypted token itself. Then, it XORs the two strings to finally produce the plaintext token.

Finally, #compare_with_real_token relies on ActiveSupport::SecureUtils to ensure the tokens are a match:

def compare_with_real_token(token, session) # :doc:

ActiveSupport::SecurityUtils.fixed_length_secure_compare(token, real_csrf_token(session))

end

And, at last, our request is authorized - you shall pass!

Conclusion

I had never given too much thought to CSRF protection before, since like so many other things in Rails, it “just works”. Every once in awhile, it’s fun to peek behind the magic curtain and see what’s actually going on.

I think the implementation of CSRF protection is a great example of separation of responsibilities in a codebase. By creating a single module and exposing a small, consistent public interface, the implementation underneath is free to change with little to no impact to the rest of the codebase — and you can see this in action as the Rails team has added new features to CSRF protection over the years, such as per-form tokens.

I learn so much every time I dive into the Rails codebase. I hope this inspires you to peek under the hood yourself next time you encounter some Rails magic!